As Women’s History Month continues to unfold, we’re delighted to highlight some of the remarkable female founders at Pear. We’re dedicated to supporting diverse entrepreneurs and are proud that 41% (and growing!) of our investments are in companies with at least one female founder. This is a truly remarkable statistic in our industry, and we take immense pride in it.

Throughout March, we’ll be featuring Q&As with some of these inspiring entrepreneurs. In this series, you’ll hear from them about their experiences in founding burgeoning startups and how they’re collaborating with Pear to turn their visions into reality.

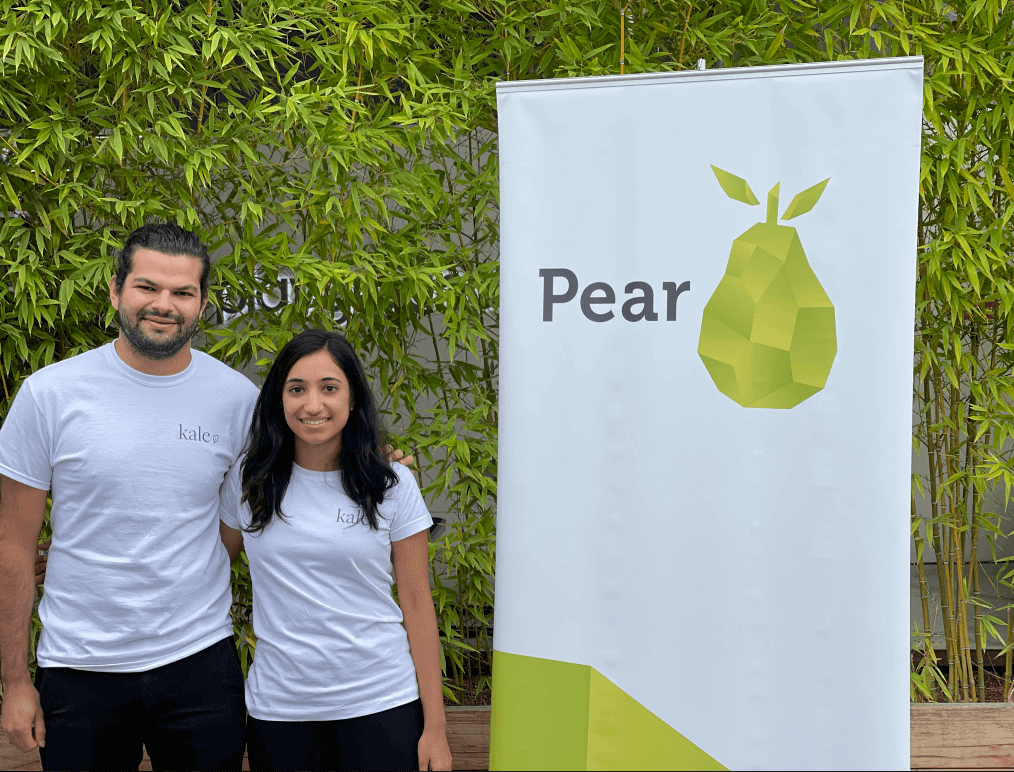

This week, we’re excited to present this Q&A between Vivien and Kale’s Co-founder Isha Patel on the journey growing Kale from the ground up. We met Kale’s Co-founders, Isha and Luis, when they were still building a startup called Palette, focused on a completely different idea. We knew they were an outstanding team from our first conversation with them, so they joined our PearX program where we explored many different ideas together – from social video apps to travel apps to superfan communities – and they ultimately landed on the idea of Kale. I’m excited to share more about Kale and their journey in this week’s installment of our Women’s History Month series!

Tell us a little bit about Kale and what problem you’re tackling.

Kale is on a mission to empower creators to translate their social value into economic value, no matter their size. They are flipping traditional influencer marketing on its head by rewarding everyday, trustworthy creators for talking about brands they actually shop at.

By tapping into authentic voices, Kale provides brands with a more cost-effective marketing channel, than FB advertising and influencer marketing. Instead of paying one influencer with one million followers, Kale makes it easy for a brand to recognize thousands of their longtail superfan customers.

What inspired you to start your own company, and what were some of the initial challenges you faced? What keeps you motivated?

Luis, my cofounder, and I sat next to each other at LinkedIn for 5 years, building and scaling video to 700M users and 30M brands. Living and breathing the small creator ecosystem for 5+ years at LinkedIn, we were blown away by the level of engagement, intimacy and clout smaller creators have among their audience.

We started talking to a bunch of creators on TikTok and Instagram, who would tell us that they had a personal relationship with each of their 3K-5K followers. We were stunned! Small creators have accrued valuable social currency over the years, but no one has figured out how to tap into them. There isn’t an efficient way for brands (who are hungry for user-generated content) to work with them at scale, while maintaining authenticity and relatability. So we started tinkering with the idea of Kale.

To me, building an impactful product means you are saving someone time, money or energy. What motivates me most is hearing that Kale does exactly that for our users: brands and creators. Plus, our team never ceases to inspire me with their drive, curiosity and creativity to tackle problems.

To me, building an impactful product means you are saving someone time, money or energy.

How did you go about securing funding for your startup and how did you evaluate potential VC partners? What advice would you give to other entrepreneurs (especially other womxn) looking to raise capital?

We went through the Pear’s Summer PearX batch in 2021. As first-time founders, we leaned on Mar to advise and guide us through the fundraising process.

Kale is something brand new. It’s a new category that sits at the intersection of social, finance and marketing. When pitching investors, we weren’t able to cleanly map ourselves as “the Uber for X” or the “Yelp for Y”. So for us, it was important to find partners who shared our vision of what a world looks like when everyday people can capitalize on their social influencers, instead of the 1% of big social media celebrities.

We found that in Kirsten Green at Forerunner, who has spent her career understanding the needs, wants and desires of really cool brands. She has an intuitive understanding of what CMOs at the modern generation of brands need at any given moment.

In Mar, we found an extension of our founding team. For example, she is in our Excel sheets with us, helping us understand the biggest business models. Plus, as a former founder, she just gets it.

At the end of the day, my opinion is that investors are not just people who cut your company a check. The impactful investors are the individuals who are the weeds with you, thinking through the business model, customer journey and market shifts.

The impactful investors are the individuals who are the weeds with you, thinking through the business model, customer journey and market shifts.

Now that you are building your team, what qualities are you looking for in potential hires?

Hiring is like deciding the invitation list to a dinner party. Each new attendee brings something to the conversation: a life lesson, previous work experience or a really warm smile. To keep the conversation dynamic, it’s crucial to have a team of diverse individuals (backgrounds, experiences, skills).

Looking back on your journey so far, what lessons have you learned that you wish someone had told you when starting out?

As a founder, get comfortable with selling as soon as you can. Figure out your own style when it comes to sales, hiring and raising capital.

Lean on other founders. To navigate murky waters, whether technical or emotional, I’ve found that other founders have an intrinsic sense of empathy.

Rewire your brain when it hears a no. You’ll hear no’s all day long: potential investors, customers and candidates will top the list. What I’ve learnt is there is no such thing as a no. Every door is left open if you are able to process “the why” behind the “no”. Each no teaches you how you can clarify your pitch. Two years into our journey, no’s are becoming even more motivating than yes’s.

Two years into our journey, no’s are becoming even more motivating than yes’s.

What advice would you give to aspiring entrepreneurs (especially womxn!) who are just starting out on their own journeys?

Go out in the world and talk to your customers. You’ll never waste time if you’re talking to potential buyers. Find the right environment to meet your customers, whether that’s at a conference, hosting an event yourself or texting a group chat of friends.

Figure out a sustainable business model. If you are B2B, try not to give away your product for free, otherwise you don’t know what your customer’s willingness to pay is. Without someone paying for your product, you don’t know if you have product-market fit. You want to hear that your price is too high or low because that informs your pricing strategy.

Finally, what’s next for Kale and why are you excited about your space and your team?

With our enthusiastic creator community and innovative brand partners, like Free People, OLIPOP and Notion, Kale is redefining how creators and brands work together on social media. We’re reinventing marketing strategies for brands who have been overly dependent on Facebook ads and influencer marketing.

We’re really excited for where we are taking our creator ecosystem – it’s going to be something really special that allows anyone who has influence to start monetizing, not just influencers!

Thank you so much, Isha. We are thrilled to be partners and cannot wait to see where Kale goes. As Women’s History Month continues, we look forward to sharing more stories from our incredible female founders and celebrating their achievements in entrepreneurship.