This is a recap of our fireside chat with Dr. Mostafa Ronaghi, SVP of Entrepreneurial Development at Illumina and founder of GRAIL, recently acquired by Illumina for $8 Billion. Watch the full talk at pear.vc/speakers, and RSVP for the next.

Dr. Ronaghi's story Biotech = data + human need Technical founders can become skilled in business Early indicators of success in early stage and Series A “Simple” advice for biotech entrepreneurs: commit

Dr. Ronaghi’s story

As a young boy growing up in Iran, Mostafa Dr. Ronaghi was drawn to biology. He figured he should become a doctor — after all, what other career options were there for someone interested in the future of genetics? But, after shadowing his uncle at a local hospital, Dr. Ronaghi discovered that medicine was not for him. Instead, he would follow his passions into the emerging field of biotechnology.

In many ways, Dr. Ronaghi was ahead of the curve. Today, opportunities are increasing within the biotech space, as technological advances continue to drive innovations forward. Decades later, the journey has taken him to roles as a researcher, serial entrepreneur, company executive, and inventor.

Since 2008, Dr. Ronaghi has served as the Senior Vice President and Chief Technology Officer at Illumina, a leading developer of life science tools. He is also a serial entrepreneur, having founded several notable biotech companies including Grail, Avantome, and Pyrosequencing AB. In all, he holds more than 30 patents.

Dr. Ronaghi earned his Ph.D. from the Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden. It was during this time that he began researching pyrosequencing methods — the groundbreaking DNA sequencing method that he would become known for.

“I started my PhD program on microbial sequencing. And after one and half years, I came up with the idea of pyrosequencing, which was a novel way of doing sequencing,” he explained.

He was later offered a role as a principal investigator at the Stanford University Genome Technology Center, and was encouraged to apply for national grants to increase funding. Because he was not a U.S. citizen at the time, Dr. Ronaghi began searching for American co-applicants to collaborate with. In 1998, the search led him to the founders of Illumina.

Biotech companies are driven by both data and human need

In biotech, metrics matter.

Dr. Ronaghi’s technological advancements in gene sequencing have allowed for faster processing and increased accuracy.

This change has been reflected in the markets as well. His work managed to reduce the cost of genome sequencing by nine orders of magnitude. Only one other industry — the semiconductor industry — has been able to accomplish this.

“Back in 1990, the cost of sequencing the human genome was more than $3 billion. And we reduced that cost to basically $1,000 within 22 years,” he said. “The genome sequencing is about $500 per genome now, in larger scales. And it’s going to go to $200 in the next few years.”

“This has kind of revolutionized healthcare, the impact is going to be enormous,” he added.

While much of the daily work responsible for a scientific breakthrough centers around minute details and microscopic particles, it’s important not to lose sight of the emotional, human elements.

When Dr, Ronaghi first started working on the science behind Grail, a healthcare company whose mission is to detect cancer early, the company’s business model was not fully determined yet. But Dr. Ronaghi and his team felt that it was unethical not to bring it to market, considering its potential to save lives.

Today, Dr. Ronaghi says the technology has improved the survival rate of cancer patients by 20%.

Technical founders can become skilled in business

Scientists and researchers shouldn’t be discouraged by the business component of biotech entrepreneurship. Dr. Ronaghi cites his own career as evidence that technical founders can learn. He encourages technical founders to try their hand at business, even if they are used to a lab.

“I feel that it is much easier to develop the technical founder to understand business than the business founder to understand the technology,” he said. “Especially if you are in a high biotech kind of a space. You really need to understand the technology and the market in depth.”

Illumina’s recent 2020 acquisition of Grail was a test of his new business mindset.

Grail was on track to go public, when Dr. Ronaghi and his team switched course and entered an $8 billion acquisition agreement with Illumina.

There were a few key elements Dr. Ronaghi considered when evaluating the deal.

First, they had to calculate the basic financials — when would the acquisition be profitable?

After justifying the suggested price, they moved on to the less tangible components of the deal — what could Illumina bring to the table?

Dr. Ronaghi realized that Illumina could help Grail scale and further expand the product into global channels. From a business perspective, the deal made perfect sense.

Early indicators for biotech success in early stage and Series A

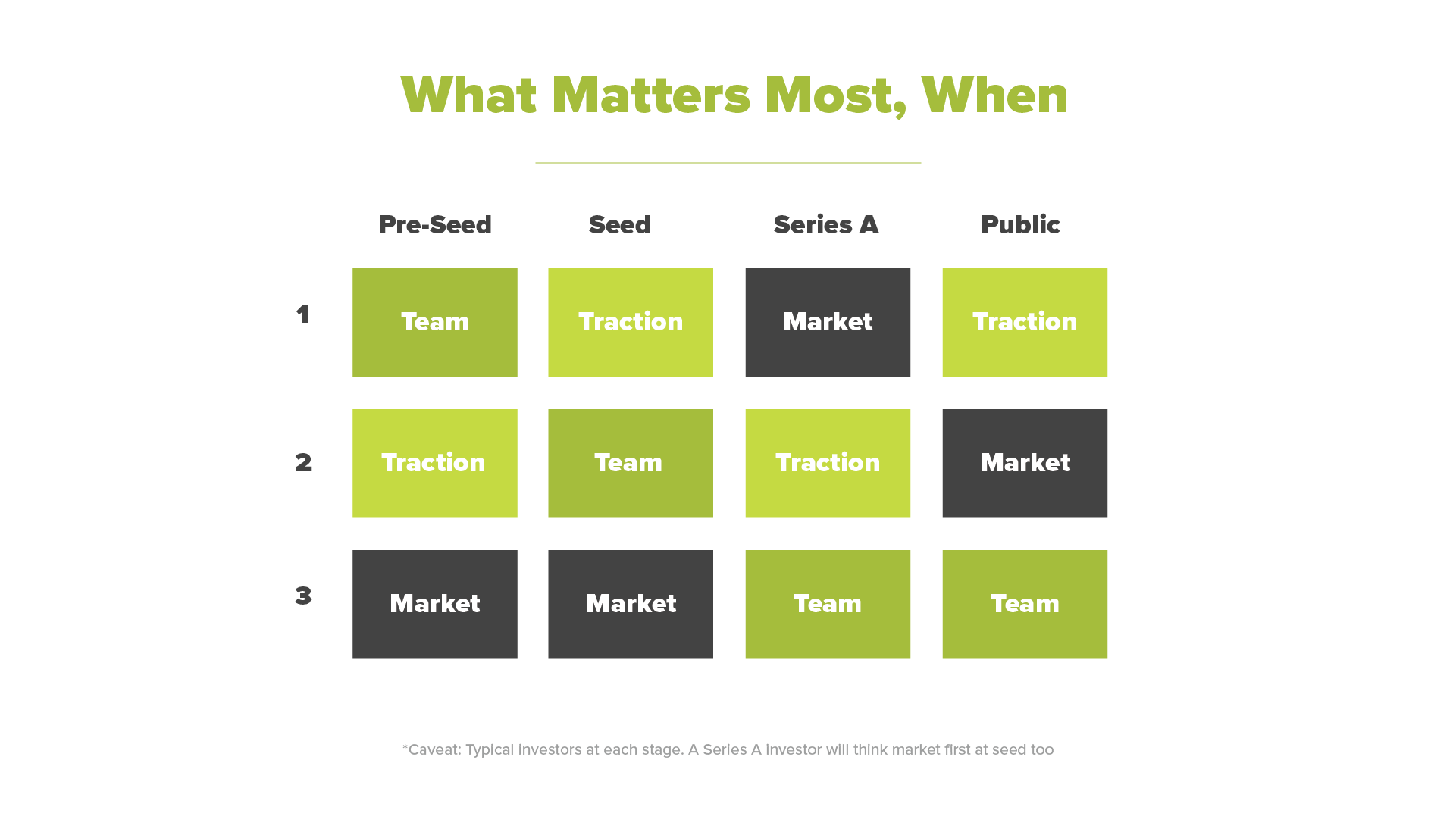

As a co-founder of Illumina Accelerator, the world’s first business accelerator focused solely on creating an innovation ecosystem for the genomics industry, Dr. Ronaghi is familiar with a company’s earliest stage. He believes the best indicator of success for an early stage company is the quality of the founding team.

“When you’re picking a company at the earliest stage, like the accelerator stage, the number one important factor is the team. There is no question,” he said.

If the team is dedicated, smart, and has the skills to create the proposed technology, then it doesn’t fully matter if the business plan is fine tuned or not.

For Series A biotech, Dr. Ronaghi has separate rules for different categories:

- For therapeutics, teams should have a lead compound identified or have pushed a product through clinical trials.

- For diagnostics, founders should be able to demonstrate that their tests work well and will have an impact on the subject.

- In the software space, there should be recognizable initial customer traction.

“Simple” advice for entrepreneurs: commit fully to your idea

Dr. Ronaghi’s advice for entrepreneurs interested in the complex biotech and life science space is relatively simple: commit fully to your business idea, and include others who will as well.

“I see that a lot of people that are in larger companies, and they want to start a company half time. That’s not going to work. You have to leave your academic job or company job and focus one hundred percent on basically creating something,” he said.

While this advice could apply to entrepreneurs in most industries, it is especially true for a field that centers around science and technological breakthroughs. Dr. Ronaghi believed that most biotech business plans had a window of opportunity that could easily be missed if the would-be entrepreneur did not quickly execute their plan.

“If you’re not dedicated yourself, you cannot convince other people to join you,” he added.

Convincing other talented individuals to join the company is key to the success of any business, Dr. Ronaghi explained. In order to accomplish this, founders should be transparent and keep their team in the loop. They also should be generous — and be prepared to give out enough equity in order to retain a great team.

Once the team and technology is in place, founders should focus on ensuring customer satisfaction and product market fit before expanding into other opportunities, he concluded.

“I understand your technology has a lot of potential. I don’t want to see it now. I want you to focus on this market and show me that you can actually deliver a fantastic customer experience.”

The future of genomics

What’s next in the world of biotech?

If Dr. Ronaghi were to make a new company now, it would be related to either of the following topics: 1) the relationship between one’s diet, microbiome, and overall health or 2) single cell biology.

“The reason that I’m picking up food is because that’s the number one environmental factor that the human body is exposed to… There are a lot of leading scientists these days that believe that 90% of diseases originate from the gut,” he said.

He views single cell biology as an area that has the potential to unlock other biotech innovations down the line.

“We have to look at biology at the cellular level or subcellular level. So single cell biology is actually very intriguing. I really think that that’s going to actually open up new frontiers in the way we are looking at medicine.”